Contrary to the simple image of wiping away dirt, professional art restoration is a rigorous discipline of applied materials science. The process is not about “cleaning” but about executing precise, reversible chemical interventions. Success hinges on a deep analysis of a painting’s chemical composition to ensure that only accumulated grime is removed, leaving the artist’s original work chemically and structurally unaltered.

The internet is filled with mesmerizing videos: a cotton swab glides across a darkened, yellowed painting, revealing a sliver of vibrant color beneath. It appears to be a simple act of cleaning, a satisfying reveal of a masterpiece hidden by time. This perception, however, belies the complex scientific reality. The “secret formula” on that swab is not a universal cleaner but a highly specific chemical solution chosen after meticulous analysis, and the person wielding it is less of a cleaner and more of a practicing chemist.

The fundamental challenge of conservation is to interact with a complex, layered chemical object—the painting—without causing irreversible harm. Each pigment, binder, and varnish layer has its own chemical properties and vulnerabilities. Treating a centuries-old oil painting as one would a dirty tabletop is a recipe for disaster. The true work of a conservator is a delicate balance of diagnostics, material science, and chemical engineering, all governed by a strict ethical code.

This article demystifies the process by exploring it through the lens of a scientist. We will examine the non-negotiable principles that guide every decision, compare the tools of the trade from solvents to lasers, and investigate how conservators address catastrophic damage. By understanding the chemistry involved, we can appreciate restoration not as a magical transformation, but as a triumph of scientific methodology.

To navigate the intricate world of art conservation, this guide is structured to walk you through the core scientific principles, the practical techniques for different types of damage, the common pitfalls, and the analytical methods used to understand a painting’s history.

Summary: How Do Restorers Clean Centuries of Grime Without Removing Paint?

- Why Must All Modern Restoration Techniques Be Fully Reversible?

- Solvent or Laser: Which Method Is Safer for Delicate Oil Paintings?

- How to Stabilize a Canvas With Severe Tears and Water Damage?

- The “Botched Restoration” Error That Ruins Historical Value Forever

- When Should You Relining a Canvas Before Structural Failure Occurs?

- Why Cheap Materials in Modern Art Will Cost You Double in Restoration?

- Fugitive Colors: Which Pigments Will Fade From Your Canvas in 10 Years?

- How to Estimate the Date of an Unsigned Painting Using Visual Clues?

Why Must All Modern Restoration Techniques Be Fully Reversible?

The single most important principle in modern art conservation is reversibility. This ethical and scientific mandate dictates that any intervention a conservator performs must be fully removable without damaging the original artwork. This is not a matter of preference but a fundamental requirement; a core tenet is that 100% of modern conservation treatments must be reversible according to current ethics standards. This principle acknowledges that future technologies and knowledge may provide better solutions, and it provides a safeguard against treatments that may, over time, prove to be harmful.

Imagine applying a protective varnish that is impossible to remove. If that varnish yellows or cracks 50 years from now, it permanently obscures or damages the painting. The principle of reversibility prevents this. It forces conservators to think not only about the immediate aesthetic improvement but also about the long-term chemical stability of the artwork. Every material added—be it an adhesive, a filler for a crack, or a new layer of varnish—must have a known method of safe removal.

This has driven significant innovation in materials science. For instance, classic consolidants like Paraloid B-72 are only chemically reversible, meaning a solvent is required to remove them, which can pose risks to the artifact. To address this, recent research has focused on developing advanced polymers with built-in thermal reversibility. These materials can be applied and later removed with controlled heat changes, offering a non-invasive alternative that fully respects the integrity of the original piece. This ongoing research underscores that conservation is a field of science, constantly seeking less intrusive and more stable solutions.

Solvent or Laser: Which Method Is Safer for Delicate Oil Paintings?

The removal of a yellowed, cracked varnish layer is perhaps the most common task in painting restoration. The two primary methods for this are solvent-based cleaning and laser ablation. The choice is not arbitrary but is determined by a rigorous chemical analysis of the varnish and the underlying paint layers. Solvents work by dissolving the varnish. A conservator uses a deep understanding of solvent polarity and solubility parameters (like the Teas chart) to select a solvent or create a gel mixture that will dissolve the aged varnish but not the original oil paint binder.

Solvent gels are a major advancement, allowing the chemical to be precisely localized, preventing it from seeping into the paint layers and giving the conservator control over contact time. The process is painstaking, often performed under a microscope, applying the solvent swab-by-swab and immediately clearing it with a non-active solvent to halt the chemical action. It is a controlled chemical reaction executed on a microscopic scale.

Laser ablation, on the other hand, uses focused light energy to vaporize the varnish layer by layer. While it offers unparalleled precision, it also carries significant risk. Each pigment has a unique light absorption spectrum and a specific damage threshold. If the laser’s energy is too high or its wavelength is incorrect for the material, it can instantly and irreversibly alter or ablate the pigment itself. For example, research on laser effects shows that the pigment Vermilion has the lowest discoloration threshold at just 0.03 J/cm², making it extremely vulnerable to laser damage. Therefore, laser cleaning is typically reserved for robust surfaces and is only performed after extensive material testing.

How to Stabilize a Canvas With Severe Tears and Water Damage?

When a painting suffers severe physical trauma like tears or water damage, the primary goal shifts from aesthetics to structural stabilization. Water can cause canvas fibers to swell and shrink, leading to deformation, while tears disrupt the very foundation that supports the paint. A conservator’s approach is methodical, treating the painting as a composite material under stress.

The first step is often to apply a temporary “facing” to the front of the painting. This involves adhering a layer of a stable material, such as Japanese washi kozo paper, with a easily reversible adhesive. This facing acts like a medical splint, securing the delicate paint layer and preventing any loss while the canvas is treated from the back. To address deformations, a heated suction table is used. This specialized equipment allows for the controlled introduction of humidity and gentle suction to relax and flatten the distorted canvas fibers without putting stress on the paint.

For tears, the repair is not a simple patch but a meticulous re-weaving process. Under a microscope, conservators perform a thread-by-thread mending, using fine, chemically inert polyester threads to bridge the gap and restore structural continuity. Any adhesives used for local repairs, such as the heat-activated BEVA 371, are chosen for their long-term stability and, crucially, their reversibility. Before any structural work, canvas pH levels are also tested to assess acidification, as a brittle, acidic canvas may require more comprehensive support to prevent future failure.

The “Botched Restoration” Error That Ruins Historical Value Forever

The term “botched restoration” evokes images of irreversible damage, a permanent loss of artistic and historical integrity. The most infamous modern example is the 2012 restoration of Elías García Martínez’s Ecce Homo in Borja, Spain. An amateur parishioner, Cecilia Giménez, attempted to “touch up” the flaking fresco, resulting in a complete overpainting that transformed the depiction of Christ into a cartoonish figure, mockingly dubbed “Monkey Christ.”

Case Study: The Ecce Homo of Borja

The “restoration” of Ecce Homo is a textbook example of what happens without scientific training. The fundamental error was the application of new, irreversible paint directly onto the original, violating the principle of reversibility. However, the story took an unexpected turn. The ruined fresco became a global internet meme, and the church saw a massive influx of tourists. As a result, the town of Borja’s tourist visits skyrocketed from 6,000 to over 57,000 annually, generating significant revenue. This bizarre outcome created a new kind of value—cultural-meme value—even as the historical art value was destroyed.

The primary error in such cases is almost always a violation of the core principles of conservation. It involves the use of inappropriate and irreversible materials, a failure to conduct preliminary analysis, and a misunderstanding of the goal, which is to conserve what exists, not to create something new. The Ecce Homo incident serves as a powerful public lesson on the difference between professional conservation and amateur repair. It demonstrates that good intentions are no substitute for scientific knowledge and methodical procedure.

When Should You Relining a Canvas Before Structural Failure Occurs?

Relining a painting involves adhering a new canvas to the back of the original to provide comprehensive structural support. For decades, this was a common treatment for aging canvases. However, in modern conservation, it is considered an extremely aggressive and last-resort intervention. The process is highly invasive: it introduces a significant amount of new material (adhesive and canvas) and can alter the original canvas texture and tension. Modern conservation practice dictates that lining should only be considered after several less invasive options have been exhausted.

The decision to reline is made only when the original canvas has lost the majority of its structural integrity and can no longer support the paint layer on its own. This may be due to widespread brittleness, extensive tearing, or severe decay from mold or moisture. Before taking such a drastic step, a conservator will first attempt to stabilize the environment, perform targeted local mends on individual tears, and consider “strip-lining”—reinforcing only the tacking edges of the canvas.

Diagnostic tools are essential in making this assessment. Raking light photography, where light is cast across the painting’s surface at a sharp angle, can map canvas deformations and planar distortions that are invisible to the naked eye. Tests of the tensile strength and brittleness of the original canvas fibers also provide quantitative data to justify the need for such a major intervention. The goal is always to preserve as much of the original material and structure as possible, and relining is the point of no return.

Why Cheap Materials in Modern Art Will Cost You Double in Restoration?

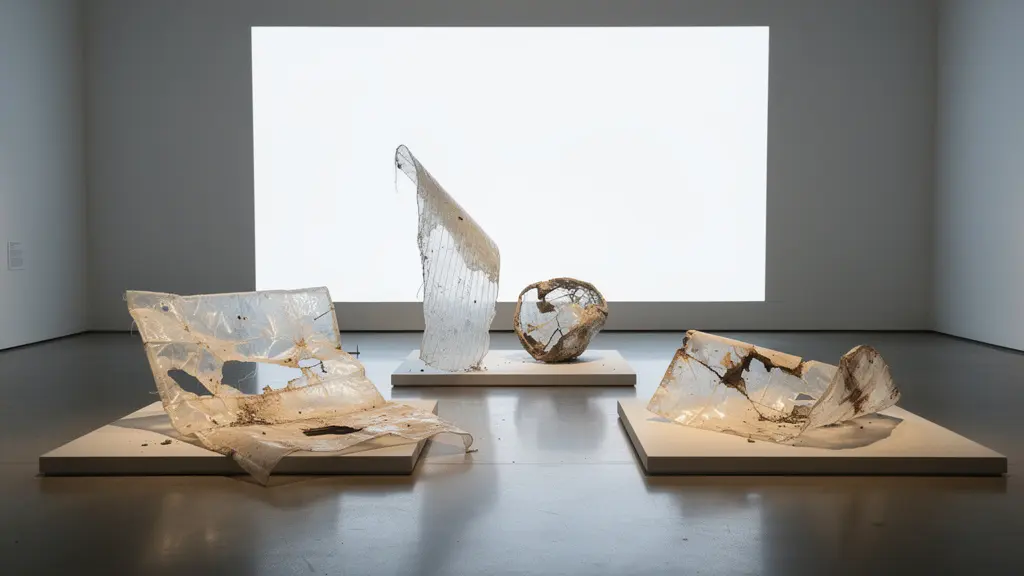

While old masters present challenges of aging, modern and contemporary art introduces a completely different set of problems rooted in the materials themselves. Many 20th and 21st-century artists intentionally used non-traditional, commercial, or experimental materials, from house paint and industrial plastics to organic matter. These materials often suffer from “inherent vice,” a term for the built-in tendency of a material to degrade due to its own chemical instability.

Unlike traditional, time-tested materials like linen canvas and linseed oil, the long-term behavior of these modern materials is often unknown and unpredictable. For example, early acrylic paints, once thought to be highly stable, are now known to be extremely soft and porous, making them magnets for dirt that becomes deeply embedded. Furthermore, conservation research has documented that certain acrylic formulations are highly susceptible to mold growth, requiring specialized and often costly removal treatments.

The conservation of plastics is another significant challenge. Many early plastics are now weeping plasticizers (oily substances), becoming brittle, or discoloring in unpredictable ways. In these cases, the conservator is not fighting external damage like dirt or a tear; they are in a constant battle against the artwork’s self-destruction. The restoration isn’t just a one-time fix but often an ongoing process of slowing down inevitable decay, making the long-term cost of conserving such pieces far higher than for traditional artworks.

Fugitive Colors: Which Pigments Will Fade From Your Canvas in 10 Years?

Not all pigments are created equal. Some, like the earth pigments (ochres, umbers), are exceptionally stable, while others are “fugitive,” meaning they are prone to fading or changing color when exposed to light. This is a critical concern in conservation, as an artist’s original color balance can be lost forever. Historically, certain beautiful but unstable pigments, like carmine lake (derived from insects), were known to fade dramatically over time, leaving once-vibrant red passages as pale ghosts.

This problem persists in modern pigments. While industrial chemistry has produced a vast range of new colors, not all have high ratings for lightfastness. An artist’s choice of a less stable but aesthetically pleasing pigment can have dramatic consequences for the artwork’s future appearance. The rate of fading depends on the pigment’s chemical structure and the cumulative amount of light exposure, particularly in the UV spectrum. A painting displayed in a brightly sunlit room can experience in decades the same amount of fading as a museum-kept piece would in centuries.

Predicting and understanding this fading is a key area of conservation science. Traditionally, this required long-term testing, but new technologies have revolutionized the process. Microfading Spectrometry is a technique where a microscopic spot on the painting is exposed to a tiny, intense beam of light while a spectrometer measures the color change in real-time. This method is virtually non-destructive, and this advanced diagnostic technology can predict 50 years of color fading in a matter of seconds. This allows conservators to identify at-risk pigments and recommend precise lighting conditions to preserve the work’s original palette for as long as possible.

Key takeaways

- Reversibility Is Non-Negotiable: Every treatment in modern conservation must be fully reversible to protect the artwork for future generations and technologies.

- Analysis Precedes Action: A conservator’s primary tool is not a cotton swab but diagnostic science. Meticulous material analysis dictates every decision, from solvent choice to structural repair.

- Material Science Is Paramount: A painting is a complex chemical object. Understanding its composition, from pigments to binders, is essential for treating not just surface dirt but also inherent degradation.

How to Estimate the Date of an Unsigned Painting Using Visual Clues?

When a painting is unsigned and its provenance is unknown, conservators and art historians become detectives. The artwork itself contains a wealth of material clues that can help place it within a specific historical period. This process is a direct application of materials science, as the materials and construction methods of art have evolved significantly over time. It’s an “autopsy” of the object, revealing its age through its physical makeup.

The investigation starts with the support structure. The canvas weave can be a primary indicator: a hand-woven linen canvas with an irregular pattern is typical of pre-19th-century work, whereas a uniform, machine-woven cotton canvas points to a later date. The wooden stretcher that holds the canvas tells a story too; simple mortise and tenon joints are characteristic of earlier periods, while keyed stretchers that allow for tension adjustments became common later. Even the tacks holding the canvas can be dated, with hand-forged tacks used before the 1800s and machine-cut tacks appearing afterward.

The paint itself provides the most definitive chemical clues. Craquelure, the network of fine cracks on the surface, can distinguish between age cracks, which tend to follow the canvas weave, and drying cracks, which are sharper and more random. Most importantly, pigment analysis using techniques like X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) can identify the specific chemical elements present, allowing for precise dating. Since many key pigments were invented at known dates, their presence—or absence—can establish a timeline. For example, the presence of Prussian Blue means the painting must be from after 1724, while Titanium White indicates it was made after 1921.

Action Plan: Dating a Painting Through Material Analysis

- Examine canvas weave pattern: Differentiate between hand-woven linen (pre-1850) and machine-woven cotton duck (post-1850) by analyzing the regularity of the threads.

- Identify stretcher construction: Look for simple, fixed mortise and tenon joints (early) versus expandable keyed stretchers (later 18th century and beyond).

- Analyze tack types: Carefully inspect the tacks or nails holding the canvas. Irregular, square-headed, hand-forged tacks suggest a pre-1800s origin, while uniform machine-cut tacks indicate a 19th-century or later date.

- Study craquelure patterns: Observe the crack network under magnification. Fine, web-like cracks that follow the canvas weave are typical of natural aging, whereas deep, sharp-edged cracks suggest issues with the paint’s drying process.

- Use XRF to identify key pigments: Conduct non-destructive X-Ray Fluorescence analysis to detect date-specific elements. The presence of Cobalt (Cobalt Blue, post-1802) or Titanium (Titanium White, post-1921) can definitively place the painting after their invention.

Ultimately, understanding the science behind art conservation transforms how we view these cultural artifacts. They are not static images, but dynamic chemical systems evolving over time. The restorer’s work is a profound act of stewardship, using scientific knowledge to silence the noise of time and allow the artist’s original voice to be heard once more. The next time you see a beautifully restored painting, you can appreciate not only the art but the meticulous science that saved it.