Feeling overwhelmed or exhausted by the end of a major exhibition is a common frustration for art lovers. The solution isn’t to see less, but to see smarter. To get the full insight from a retrospective, you must shift your mindset from a passive visitor to an active ‘curatorial detective.’ This guide provides the strategic framework to deconstruct the exhibition’s narrative, manage your energy, and uncover the deeper story the artist and curators intended to tell.

There’s a familiar feeling for any dedicated art lover: you’ve spent hours immersed in a blockbuster retrospective, and as you enter the final gallery, a wave of exhaustion hits. The brilliant late works of a master blur into a haze of “museum fatigue.” You’ve seen everything, but you’re not sure what you’ve truly understood. The standard advice—research the artist, read the wall text, avoid the crowds—only scratches the surface. This approach treats a visit like a checklist to be completed rather than an experience to be absorbed. A retrospective, which serves as a comprehensive overview of an artist’s entire career, is one of the highest honors in the art world, designed to solidify an artist’s legacy. It deserves more than a passive walkthrough.

But what if the key wasn’t simply consuming information, but actively investigating it? The true way to prepare for a retrospective is to transform yourself into a curatorial detective. Your mission is not just to look at paintings on a wall, but to uncover the hidden narrative arc—the story of struggle, breakthrough, and evolution that connects the first room to the last. It’s a method of engaging with art that prioritizes strategic observation over exhaustive viewing, turning a potentially overwhelming event into a profound and personal journey.

This guide will equip you with the tools for this investigation. We will explore how to decode an artist’s early work, make strategic choices about audio guides, understand the artist’s final statements, and navigate the practical challenges of pacing and crowds. By adopting this active mindset, you will not only see the art differently but also leave the exhibition with a lasting, coherent understanding of the artist’s entire life’s work.

To help you navigate this deep dive into an artist’s world, this article is structured to build your skills as a ‘curatorial detective.’ The following sections offer a complete toolkit for transforming your next museum visit.

Summary: Unlocking the Full Story of a Retrospective Exhibition

- Why Is Seeing an Artist’s Early “Failures” Crucial to Understanding Their Fame?

- Audio Guide or Silence: Which Offers a Better Connection With the Art?

- What Does the “Late Style” Reveal About an Aging Master’s Mind?

- The Pacing Error That Makes You Hate the Last Room of a Large Show

- How to Navigate a Crowded Blockbuster Show to See the Hits Unobstructed?

- Why Does Lighting Design Make or Break the Viewer’s Emotional Arc?

- What Are the Best Visual Aids for Mastering Art Periods Quickly?

- How to Visit a Commercial Art Gallery Without Feeling Intimidated?

Why Is Seeing an Artist’s Early “Failures” Crucial to Understanding Their Fame?

The first room of a retrospective is often the quietest, filled with the artist’s formative, sometimes awkward, early works. Many visitors rush through, eager to get to the “famous” pieces. This is a critical error. These early creations are the first chapter of the story, the foundation upon which the entire artistic journey is built. They reveal the artist’s initial influences, their struggles with technique, and the nascent themes that will obsess them for a lifetime. To understand the genius of the masterpiece, you must first appreciate the journey from apprenticeship and the so-called “failures” that paved the way.

These early works provide essential context. They are the baseline from which all subsequent innovation can be measured. Consider that Vincent Van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime; his most celebrated works were, in a commercial sense, failures. Seeing his dark, earthy paintings of Dutch peasants before the explosion of color in Arles allows you to witness his personal and artistic transformation. It’s not just a change in style; it’s a revolution you can see happening before your eyes.

This struggle for recognition is a common thread. The great modernist Paul Cézanne was the primary inspiration for the failed painter character in his friend Émile Zola’s 1885 novel *L’œuvre*. The real-life artist was so far from the mainstream that he didn’t receive his first solo exhibition until he was 56 years old. By viewing these early, often-rejected works, the “curatorial detective” gathers the first clues, understanding that fame is not a sudden event but the culmination of a long, often difficult, process of discovery.

Audio Guide or Silence: Which Offers a Better Connection With the Art?

The question of whether to use an audio guide is more than a simple preference; it’s a strategic choice that fundamentally alters your relationship with the art. There is no single right answer, as the ideal approach depends on your goal. An audio guide offers the official curatorial narrative, providing invaluable context and pointing out details you might otherwise miss. However, it can also create a passive experience, tethering your thoughts to a pre-packaged script and preventing you from forming your own, more personal connection with the work. The sophisticated visitor doesn’t just choose “yes” or “no”—they choose a strategy.

Instead of a binary choice, consider a more flexible approach to listening. An effective “curatorial detective” might employ one of several methods:

- Hybrid Strategy: Use the audio guide for a few pre-selected “anchor” artworks to grasp the main curatorial arguments. Once you understand the exhibition’s key themes, remove the headphones and explore the surrounding works in silence, using your newfound knowledge to build your own interpretations.

- Active Listening Method: Don’t just passively absorb the audio guide’s commentary. Actively question its interpretation. Ask yourself: What perspectives might be missing? Is there an alternative reading of this piece? This turns the guide from a lecture into a dialogue.

- Personalized Soundscape: For a purely emotional connection, forgo the official guide and create your own audio environment. Listening to music contemporary to the artist’s period through your own headphones can create a powerful, immersive experience that connects you to the art on a visceral level.

As the image suggests, there is a deep power in silent, personal contemplation. Choosing silence allows your eyes to wander freely and your mind to make connections unprompted by a narrator. It fosters a direct, unmediated conversation between you and the artwork. The ultimate goal is to find the right balance, using the audio guide as a tool to open doors, not as a script that dictates your entire journey through the exhibition.

What Does the “Late Style” Reveal About an Aging Master’s Mind?

The concept of an artist’s “late style” is often romanticized, characterized by a newfound freedom, a loosening of technique, or a turn towards the spiritual. Think of Titian’s flickering brushstrokes or Rembrandt’s profound, introspective self-portraits. While this is often true, late style can also manifest in darker, more complex ways: through obsession, repetition, and even the violent destruction of one’s own work. These acts are not signs of failure but can be the ultimate expression of an artist’s lifelong pursuit of an unattainable ideal, revealing a mind that is still wrestling with its core questions.

The final rooms of a retrospective can showcase this intense, often brutal, self-editing process. It is the artist’s last word, their final attempt to control their legacy and distill their vision to its absolute essence. For some, this means creation; for others, it means erasure. This act of “creative destruction” is a powerful form of late-style expression, where the artist’s final judgment on their own work becomes the work itself.

Francis Bacon’s Destructive Creation

The painter Francis Bacon was notorious for his torturous creative process. He saw creation and destruction as inextricably linked. After his death in 1992, his famously cluttered studio was painstakingly excavated by archaeologists and art historians. Within the chaos, they discovered nearly one hundred slashed, cut, and discarded canvases. Bacon routinely destroyed any work he felt was unsuccessful or had not captured the raw “image” he was chasing. This act of destruction wasn’t an afterthought; it was an integral part of his method, a final, violent brushstroke that reveals a relentless, self-critical mind at the peak of its powers.

When you encounter an artist’s late work, look beyond just the painted surface. Consider what is not there. Think about the decades of work that led to this final, distilled statement. The late style of an aging master is not always a peaceful resolution; sometimes, it is the beautiful, haunting evidence of a battle fought until the very end.

The Pacing Error That Makes You Hate the Last Room of a Large Show

It’s the paradox of the blockbuster exhibition: the more there is to see, the less you often feel you’ve absorbed. This phenomenon, known as “museum fatigue,” is not a sign of disinterest but a genuine cognitive and physical exhaustion. The human brain can only process so much visual information before it begins to shut down. Decision fatigue sets in from constantly choosing where to look next, and physical tiredness from hours of standing and walking takes its toll. The common mistake is to treat an exhibition like a marathon to be endured, rather than a series of sprints with planned recovery.

An undisciplined, linear walkthrough is a recipe for burnout. You arrive with high energy, spend too much time in the early rooms, and are left with nothing for the grand finale, where the artist’s most mature and often most profound works are displayed. To combat this, the “curatorial detective” must become a master of strategic pacing. This means abandoning the idea that you must see everything and instead creating a deliberate plan of attack that preserves your most valuable resource: your attention.

Your Action Plan to Conquer Museum Fatigue

- The Inverted Visit Strategy: Start with the final room. See the culmination of the artist’s career with fresh eyes and a clear mind. Then, work your way backward. This transforms the visit into a “forensic investigation,” where you trace the origins of the masterpieces you’ve just seen.

- The Triage Method: Before you enter, use the exhibition map to pre-select a maximum of five “must-see” rooms or artworks. Give yourself permission to consciously skip or walk quickly through other sections. This prevents decision fatigue and ensures you have the energy for what matters most to you.

- The Strategic Mid-Show Reset: Pacing isn’t just about what you see, but also when you rest. Plan a deliberate 20-minute break in a courtyard, café, or quiet bench after you’ve viewed about half the exhibition. This clears your mental palate and allows you to return to the second half refreshed and re-focused.

By treating your visit as a strategic mission rather than an exhaustive march, you take control of your experience. You ensure that you arrive at the final room not with exhaustion, but with the energy and clarity needed to appreciate an artist’s ultimate achievements.

How to Navigate a Crowded Blockbuster Show to See the Hits Unobstructed?

A blockbuster retrospective for a world-renowned artist can feel less like a cultural pilgrimage and more like a battle for territory. With the Louvre welcoming nearly 8.9 million visits in 2023, the world’s most popular museums are defined by crowds, especially around iconic masterpieces. The desire to get a clear, unobstructed view can lead to frustration and a diminished experience. However, a savvy visitor doesn’t compete with the crowd; they use its rhythms and patterns to their advantage. Navigating a packed gallery is a skill, one that requires patience, observation, and a set of counter-intuitive techniques.

The key is to abandon the “head-on” approach. Pushing through the scrum to get to the front is stressful and rarely yields more than a fleeting, jostled glimpse. Instead, adopt the mindset of a strategist, observing the flow of people and identifying opportunities. The crowd is not just an obstacle; it’s a dynamic system you can learn to navigate. The following table outlines three core techniques for seeing what you came to see, even on the busiest days.

| Technique | Best For | Key Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Tidal Flow | Masterpiece viewing | Enter space as large groups exit |

| Planet and Moons | Context building | Explore surrounding works first |

| Peripheral Vision | Overall composition | Stand back from crowds for macro-view |

The Planet and Moons technique is particularly effective. While the crowd orbits the “planet” (the masterpiece), you explore the smaller, often-overlooked “moons” (surrounding works) in relative peace. This not only gives you something interesting to look at while you wait but also provides crucial context for the main event. When you notice the main cluster of people beginning to dissipate (the “Tidal Flow”), you can then move into the vacated space for a calmer, more meaningful encounter with the masterpiece.

Why Does Lighting Design Make or Break the Viewer’s Emotional Arc?

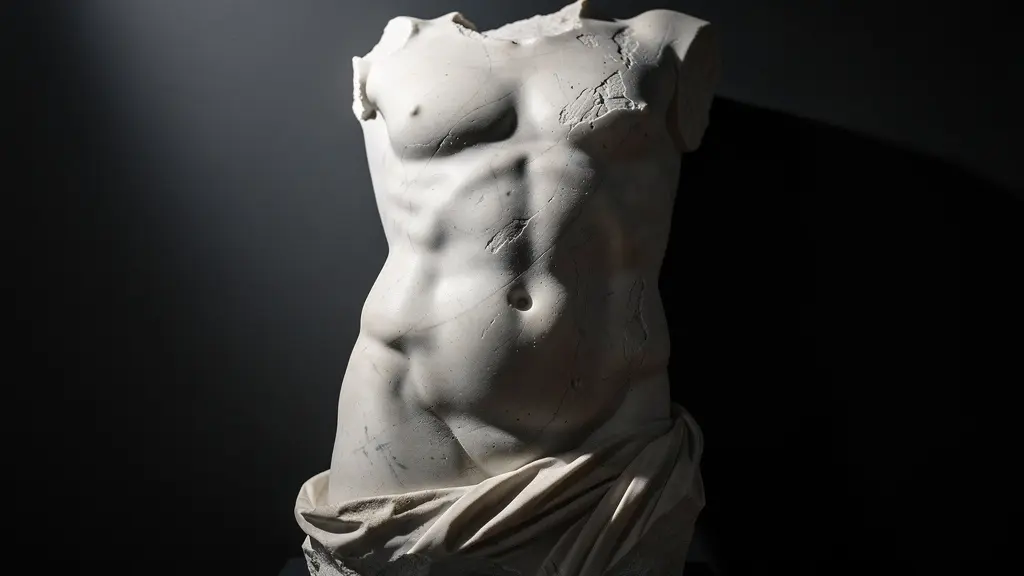

Lighting in a museum is far more than simple illumination; it is one of the most powerful and subliminal tools a curator has. It directs the eye, models form, renders color, and, most importantly, orchestrates the viewer’s emotional journey through the exhibition. A subtle shift in the angle, intensity, or color of a light can transform a painting from flat to vibrant or a sculpture from static to dynamic. Bad lighting can deaden a masterpiece, while brilliant lighting can make it sing. For the “curatorial detective,” learning to notice the lighting is like learning to hear the exhibition’s hidden musical score.

The technical precision involved is immense. Curators and lighting designers work to find the perfect balance between visual impact and conservation. A recent study on museum environments found that a color temperature of 4500K CCT provides the highest visual comfort for viewers, but this is often adjusted based on the specific artwork. The choice between warm and cool light, for instance, is a deliberate decision to evoke a specific mood. Warm light (around 2700K-3000K) creates a sense of intimacy and historical authenticity, often used for Old Master paintings or period rooms to evoke the feel of candlelight. In contrast, cool light (4000K-5000K) feels crisp and modern, providing clarity and energy for contemporary art or scientific displays.

Beyond color, the direction and focus of light create drama. The use of a strong spotlight from above, as seen in the image, creates deep shadows—a technique known as chiaroscuro. This doesn’t just reveal the sculpture’s form; it imbues it with a sense of mystery and emotional weight. The next time you’re in a gallery, pay attention. Is the entire room brightly lit, encouraging a comparative, academic viewing? Or is each work lit individually, like an actor on a stage, creating a series of intimate, dramatic encounters? The lighting is telling you how to feel.

What Are the Best Visual Aids for Mastering Art Periods Quickly?

A major retrospective often spans multiple art historical periods, and understanding the shifts between them is crucial to appreciating the artist’s innovations. Simply memorizing a chronological list of movements—Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, Romanticism—is dry and ineffective. The brain learns best through connection and comparison, not rote memorization. To truly master these periods, the “curatorial detective” needs active learning tools that transform abstract timelines into tangible, memorable visual stories.

The goal is to move beyond passive reading and engage in active analysis. Instead of just learning that Impressionism was followed by Post-Impressionism, you need a method to *see* and *feel* that transition. This involves creating your own visual aids that highlight change over time and connect art to a broader cultural context. These are not tools for casual viewing but for deep, focused study that pays dividends in your ability to quickly situate any artwork within the grand narrative of art history.

Here are three powerful strategies for building your art historical framework:

- Comparative Diptych Method: Don’t just look at works in isolation. Create your own digital side-by-side pairings. Place a High Renaissance portrait next to a Mannerist one, or a Realist landscape next to an Impressionist one. This act of direct comparison makes the stylistic shifts in color, composition, and subject matter instantly and unforgettably clear.

- Architectural Anchoring: Art is not made in a vacuum. A powerful mnemonic technique is to link art movements to the dominant architectural styles of the same period. Imagine a Bernini sculpture inside a grand Baroque church, or a Fragonard painting within an intimate Rococo salon. This creates a 3D “memory palace” that provides a rich, immersive context for each movement.

- Thematic Timelines: Instead of a generic timeline of “-isms,” track a single subject across multiple periods. Follow the depiction of the human figure from the idealized forms of Neoclassicism, through the emotional drama of Romanticism, to the fragmented bodies of Cubism. This thematic thread makes the evolution of artistic concerns concrete and easy to follow.

Key Takeaways

- Adopt a “Curatorial Detective” mindset: Your goal is to investigate the narrative, not just see the sights.

- An artist’s early “failures” are the essential first chapter; they provide the baseline for understanding their later genius.

- Manage your energy as a strategic resource by planning your visit, taking breaks, and giving yourself permission to skip rooms.

How to Visit a Commercial Art Gallery Without Feeling Intimidated?

After honing your analytical skills in a museum, stepping into the stark, silent “white cube” of a commercial art gallery can feel like an entirely different challenge. The lack of crowds, the presence of a gallerist, and the implicit context of commerce can be intimidating. However, the investigative mindset you’ve developed is perfectly suited for this environment. The key is to reframe your role: you are not an intruder or a potential buyer to be judged. You are a researcher, gathering information and engaging with the forefront of contemporary art.

This sense of intimidation is often rooted in the art world’s very real accessibility issues; data shows that 84% of frequent museum-goers identify as white, highlighting how these spaces can feel exclusive to many. By adopting a specific persona and strategy, you can reclaim your right to be in that space, regardless of your intention to purchase. The white cube itself is not meant to be intimidating; its purpose is to eliminate all distractions, focusing your attention entirely on the art. Seeing it as a tool, rather than a barrier, is the first step.

To navigate this space with confidence, arm yourself with a simple plan:

- Adopt the Researcher Persona: This mental shift is your most powerful tool. You are there to learn about the artist, to understand their place in the current art conversation, and to see new work. This changes the power dynamic; you are not being evaluated, you are conducting an evaluation.

- Prepare Three Smart Questions: Having a few open-ended questions ready can break the ice and open a meaningful conversation with the gallerist. Avoid “how much is this?” and instead ask things like, “How does this body of work connect to the artist’s previous series?” or “What conversations are happening around this artist’s work right now?” This signals genuine interest and expertise.

- Engage with the Provided Materials: Always pick up the press release or checklist. It’s your primary clue sheet, containing the artist’s statement, an essay by a curator, and details about the works. It’s a free, invaluable piece of research material.

By shifting from a passive viewer to an active investigator, you equip yourself with a permanent toolkit for engaging with art. This approach transforms any exhibition, from a sprawling retrospective to an intimate gallery show, into a rich, rewarding experience. You no longer just see art; you understand the story behind it, the choices that shaped it, and your own personal connection to it. Your next gallery visit is not an exam to pass, but an adventure to be undertaken.