Contrary to popular belief, Renaissance artists didn’t just copy ancient statues; they repurposed the classical form to make a radical new philosophical argument.

- The shift to realism wasn’t the goal itself, but the medium for expressing humanist ideals like intellect, potential, and individual dignity.

- The nude body was transformed from a medieval symbol of shame into a “vessel of virtue,” representing the peak of divine creation on Earth.

Recommendation: Look beyond the anatomical accuracy in Renaissance art and see the body as a painted argument for the central importance of humanity in the cosmic order.

When we gaze upon a Renaissance painting, we are often struck by the startling realism of the human form. The weight of a figure, the turn of a muscle, the individual character in a face—all seem to mark a definitive break from the flat, ethereal figures of the medieval era. The common explanation points to a “rebirth” of classical antiquity, a rediscovery of Greek and Roman models. While true, this explanation remains on the surface. It tells us what happened, but not why it mattered so profoundly.

The real revolution was not aesthetic; it was philosophical. The rise of Humanism in 14th and 15th-century Italy prompted an epistemological earthquake. It repositioned humanity not as a fallen creature mired in sin, but as a being of immense potential and dignity, the “measure of all things.” This was not a rejection of God, but a new way of finding the divine within the human. Artists, sponsored by patrons steeped in this new learning, were at the forefront of this revolution. They were tasked with a monumental challenge: how to make this abstract philosophical dignity visible?

Their answer was the human body. It became the ultimate canvas, a manifesto for a new worldview. The shift towards anatomical study, the embrace of the nude, and the development of mathematical perspective were not mere technical exercises. They were tools to construct a new kind of image, one that argued for the rational, noble, and central place of the individual. The body was no longer just a character in a holy story; it became the story itself, a vessel of virtue and a testament to human potential.

This article explores this profound transformation. We will dissect how humanist philosophy was translated into paint and plaster, moving from the motivations of patrons to the very chemistry of the materials artists used. We will uncover how the body became the focal point for expressing everything from civic power to a new, more intimate relationship with the divine.

For those who prefer an academic perspective, the following lecture provides a deep dive into the mind of a key figure of this era, Leonardo da Vinci, and his connection to humanism. It offers a scholarly complement to the philosophical and artistic explorations within this guide.

To fully grasp how these ideas unfolded, this article examines the specific mechanisms—patronage, technique, and ideology—that shaped this new vision of the human form. The following sections break down the key questions and innovations that defined the era.

Table of Contents: The Humanist Body in Renaissance Painting

- Why Did the Medici Family Spend Fortunes on Public Art in Florence?

- How to Spot the Use of Linear Perspective in Early Renaissance Works?

- Oil vs. Fresco: How Climate Dictated the Style of the Renaissance?

- The Myth of the “Sudden Rebirth” That Ignores Medieval Innovations

- What Are the 5 Must-See Chapels for Understanding the High Renaissance?

- How to Paint the Nude Today Without Objectifying the Subject?

- How Does Lime Plaster Lock Pigment Into the Wall Crystal Structure?

- Why Did Western Art Focus on Mimesis While Others Chose Abstraction?

Why Did the Medici Family Spend Fortunes on Public Art in Florence?

The Florentine Renaissance was not merely an artistic movement; it was a political project. For families like the Medici, art was the most potent form of public relations and a tangible display of their humanist values. Spending vast sums on chapels, paintings, and sculptures was not an act of simple piety or extravagance. It was a strategic investment in cultural capital that solidified their power, portraying them as sophisticated, enlightened rulers who embodied the civic virtues of the republic. By commissioning works that celebrated human dignity and intellectual achievement, they fused their family’s identity with the very ideals of the Renaissance.

The scale of this investment was staggering. It is documented that Lorenzo de Medici spent an estimated 663,000 florins on art and architecture, a sum equivalent to hundreds of millions of dollars today. This expenditure was not hidden away in private villas but was directed towards public-facing projects, primarily churches and piazzas. This act of “public largesse” was a calculated performance of civic duty, demonstrating that their wealth served the entire city of Florence. It transformed money, often earned through the morally ambiguous practice of banking, into a legacy of beauty and intellectual prestige.

This strategy was a physical manifestation of their authority, embedding their presence into the very fabric of the city. As historian Dale Kent observes in her work on the family’s patronage:

The Medici building programme in the parish of San Lorenzo from the late twenties on may be seen as a tangible expression of their growing power and influence.

– Dale Kent, Cosimo de’ Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron’s Oeuvre

Ultimately, Medici patronage was a masterclass in soft power. By funding art that championed the humanist body—rational, beautiful, and heroic—they were effectively commissioning an idealized portrait of their own governance. The art they paid for was a constant, public argument for why they were fit to lead, transforming Florence into a living museum of their political and philosophical ambitions.

How to Spot the Use of Linear Perspective in Early Renaissance Works?

Linear perspective was more than a technical trick for creating realistic depth; it was a philosophical statement. By organizing a painted scene along a logical, mathematical grid that converges to a single vanishing point, it positioned the viewer as a rational, stable observer. The world depicted in the painting was constructed specifically for the intellectual gaze of the person standing before it. Spotting its use involves looking for the tell-tale signs of this new, ordered vision: architectural elements that act as guides for the eye.

To identify linear perspective, search for orthogonal lines—lines that are perpendicular to the picture plane but appear to recede into the distance, like the edges of a tiled floor, the tops of columns, or the coffers of a ceiling. In a painting using correct perspective, all these lines will converge at a single vanishing point located on the horizon line. This creates a powerful illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Early Renaissance artists used this system to place their human subjects within a coherent, measurable, and human-centric world.

The revolutionary impact of this technique is perfectly demonstrated in one of the earliest and most famous examples.

Case Study: Masaccio’s Holy Trinity – A Hole in the Wall

In Masaccio’s fresco The Holy Trinity (c. 1427), the use of perspective was so groundbreaking that it stunned his contemporaries. He painted a coffered barrel vault with such mathematical precision that its orthogonal lines all converge at a single vanishing point. Crucially, this point is located at the base of the cross, at the average viewer’s eye level (around 5’3″). This strategic placement pulls the viewer directly into the scene, making the painted chapel appear as a real, physical extension of the church itself. The art historian Giorgio Vasari famously wrote that it seemed to create “a hole in the wall.” This was humanism in action: using mathematics to subordinate divine mystery to the rational perception of the human observer.

Look for this alignment of architecture and viewer. When you find receding parallel lines that meet at a single point, you are witnessing the moment art became a science, and the world within the frame was rebuilt around the human eye.

Oil vs. Fresco: How Climate Dictated the Style of the Renaissance?

The choice of medium is never neutral; it profoundly shapes what an artist can express. During the Renaissance, the two dominant techniques—fresco in Italy and oil paint in Northern Europe—were largely dictated by climate. Italy’s dry, warm conditions were ideal for fresco painting on large plaster walls, while the damp, cool climate of the North favored the slow-drying, meticulous work of oil on transportable wood panels. This climatic divergence created two distinct paths for representing the humanist body.

Fresco (from the Italian for “fresh”) involves applying pigment to wet lime plaster. The chemical reaction binds the color into the wall itself as it dries, creating a durable, matte surface. However, it demands incredible speed and confidence, as the plaster dries within a day, allowing for no corrections. This led to a style characterized by broad forms, clear outlines, and an emphasis on monumental, idealized bodies suited for grand public narratives. The body in fresco is often a universal type, a vessel for a clear moral or religious idea.

Oil paint, in contrast, offered artists time and flexibility. Pigments mixed with oil dry over days or even weeks, allowing for extensive blending, layering (glazing), and minute corrections. This slow process enabled an unprecedented level of detail and a focus on texture, light, and individual psychology. Northern artists like Jan van Eyck could render the specific—the glint of light on armor, the soft texture of fur, and the unique, imperfect features of a specific person. The body in oil paint is hyper-individualized, a study of a particular human in a particular moment.

The fundamental differences between these techniques directly influenced how the humanist interest in the individual was expressed. One celebrated the ideal and public body, the other the specific and private one. A comparative look at their properties reveals this stylistic split.

| Technique | Oil Paint | Fresco |

|---|---|---|

| Drying Time | Slow (days to weeks) | Fast (hours) |

| Blending Capability | Excellent – allows sfumato | Limited – requires quick work |

| Detail Level | Extreme precision possible | Generalized forms |

| Corrections | Can rework repeatedly | No changes once dry |

| Body Representation | Hyper-specific, individual features | Idealized, universal types |

Your Checklist: Distinguishing Oil from Fresco

- Examine the surface texture: oil paintings often show brushstrokes and impasto, while frescoes appear flat and matte.

- Look for translucency in skin tones: oil allows for luminous, layered glazing for flesh, whereas fresco produces more opaque, solid colors.

- Check for detail in hair and fabric: oil permits the rendering of individual strands and threads; fresco typically shows broader masses of form.

- Observe color transitions: oil painting is famous for smooth, smoky gradations (sfumato), while fresco often shows more distinct boundaries between colors.

- Assess the support material: oil is typically on canvas or a wood panel, but fresco is always part of a plaster wall or ceiling.

The Myth of the “Sudden Rebirth” That Ignores Medieval Innovations

The term “Renaissance” itself, meaning rebirth, promotes a powerful but misleading myth: that the Middle Ages were a long, dark slumber from which art was suddenly awakened by the rediscovery of classical antiquity. This narrative, popularized by 19th-century historians, conveniently ignores the fact that the key elements of Renaissance humanism—an interest in naturalism, human emotion, and physical weight—were already developing throughout the late Gothic period. The Renaissance was not a revolution out of nowhere, but the powerful culmination of ideas that had been brewing for centuries.

Artists like Giotto, often hailed as the “father of the Renaissance,” did not appear in a vacuum. His work, which brought a new sense of gravity and emotional depth to human figures around 1305, can be seen as a product of his time, not a rejection of it. This perspective requires us to re-examine the supposed “darkness” of the medieval era.

Re-frame Giotto not as a sudden break, but as the culmination of medieval theological trends, particularly the Franciscan emphasis on Christ’s humanity and suffering.

– Hugh Honour and John Fleming, Renaissance Humanism and Medieval Continuity

This Franciscan movement, which began in the 13th century, encouraged believers to emotionally connect with the life and suffering of Christ and the saints. This required a new kind of art—one that made the divine feel human and relatable. Giotto’s weighty, expressive bodies were the perfect visual answer to this new theological realism. His innovations were driven by contemporary Christian thought, not just by looking at ancient Roman statues.

Case Study: The Bridge from Gothic to Renaissance

Decades before the “official” start of the Renaissance, late Gothic art was already exploring a new naturalism. The work of the Limbourg brothers, particularly their illuminated manuscript the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412-1416), is a stunning example. It features detailed, atmospheric landscapes with realistic depictions of changing seasons, and its figures display individualized faces, naturalistic movement, and clear psychological states. These innovations in depicting the body in a believable space and time were not a prelude to the Renaissance; they were an integral part of the same evolving humanist interest in the observable world.

To truly understand the Renaissance, we must see it as an acceleration and intensification of existing trends, not a clean break. The human body had been slowly re-emerging as a subject of artistic and theological importance long before the Medici came to power. The “rebirth” was, in fact, the blossoming of seeds planted deep in the medieval soil.

What Are the 5 Must-See Chapels for Understanding the High Renaissance?

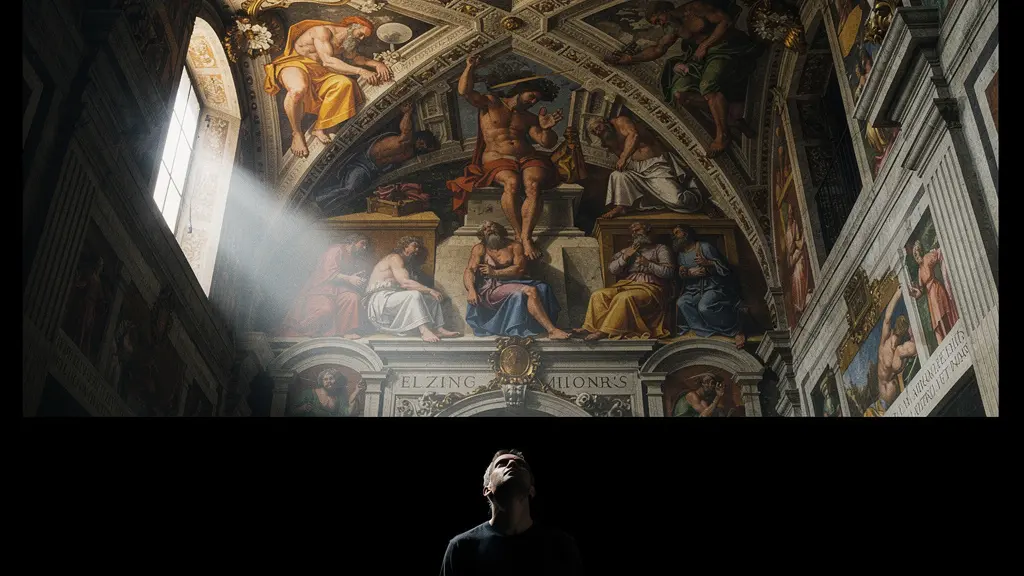

The chapel, a private space for worship within a larger church, became the ultimate laboratory for High Renaissance artists to explore the full potential of the humanist body. Funded by wealthy patrons, these spaces were transformed into complex theological and philosophical arguments, with the human form as the primary vocabulary. To visit these chapels is to walk through a visual encyclopedia of humanist thought, where bodies are used to express everything from divine power to Neoplatonic philosophy.

In these immersive environments, figures are not merely decorative. Their poses, musculature, and interactions create a dynamic narrative that envelops the viewer. From Michelangelo’s superhuman nudes to Raphael’s poised philosophers, the painted and sculpted bodies on these walls represent the peak of an ideology that saw humanity as the beautiful, rational center of God’s creation. Each chapel offers a unique lesson in how the body was used as a vessel for complex ideas.

Exploring these five key sites provides a comprehensive education in how High Renaissance masters used the human form to articulate the era’s most profound beliefs:

- Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua (c. 1305): Though technically pre-Renaissance, Giotto’s work here is the essential starting point. He pioneers emotional expression through body language, giving his figures a psychological weight and solidity that broke from Byzantine tradition.

- Brancacci Chapel, Florence (1424-1427): Masaccio’s frescoes mark the true beginning of the Renaissance painting. His figures, like Adam and Eve, have a palpable sense of gravity and physical presence, their bodies reacting to the world with anatomical and emotional realism.

- Sistine Chapel, Vatican City (1508-1512): Michelangelo’s ceiling is the zenith of the humanist body. His ignudi (nude youths) are not biblical characters but superhuman allegories of the soul, representing the Neoplatonic idea of the body as the beautiful earthly form that yearns for divine reunion. This is the concept of corporeal dignity made manifest.

- Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican City (1509-1511): In his School of Athens, Raphael uses the bodies of philosophers to create a visual map of intellectual history. Each pose and gesture is a carefully choreographed representation of a specific philosophical school, turning the human form into a carrier of abstract thought.

- Medici Chapel, Florence (1520-1534): Here, Michelangelo’s sculptures of Day, Night, Dusk, and Dawn use the human body as a metaphor for the passage of time and the cycle of life. The powerful, contorted musculature conveys a sense of struggle and melancholy (terribilità), reflecting the turbulent end of the High Renaissance.

These chapels are not just collections of paintings; they are complete, immersive arguments. They demonstrate the final evolution of the humanist body in art—a form capable of expressing the entire spectrum of human experience, from rational thought to divine aspiration.

How to Paint the Nude Today Without Objectifying the Subject?

The Renaissance, in celebrating the artist as a divinely inspired “genius,” established a power dynamic in the studio that has persisted for centuries: the active, male creator and the passive, often female, nude object. While humanism celebrated the idealized body, it often did so at the expense of the individual’s agency. Contemporary artists working with the nude are acutely aware of this problematic legacy. The modern challenge is to engage with the tradition of figure painting while actively dismantling its inherent objectification, shifting the focus from the idealized “nude” to the authentic “naked” individual.

This requires a conscious move away from the artist-as-master paradigm towards a more collaborative and ethical practice. The goal is no longer simply to capture a form, but to represent a person, with their consent, narrative, and subjectivity intact. As one study on modern practices notes, the very structure of the artist-subject relationship is being re-evaluated.

Humanism, by celebrating the artist as ‘genius’, created an imbalance of power in the studio. Contemporary practices seek to rebalance this by demystifying the artist’s role and emphasizing the relationship and consent between artist and subject.

– Contemporary Art Ethics Study, Modern Approaches to Figure Painting

Today, painting the nude ethically involves a set of strategies designed to empower the subject and ensure the process is one of mutual respect and co-creation. This approach transforms the act of painting from an act of observation into a dialogue. Key strategies include:

- Establishing a collaborative dialogue: The model is no longer a silent prop. Artists engage in conversation about the pose, the setting, and the intended meaning of the final work, making the model an active participant in their own representation.

- Focusing on authentic representation: The aim is to depict a specific person in their own skin, rather than forcing them into a pre-conceived ideal of beauty or a classical trope.

- Incorporating the model’s narrative: Some artists document the model’s own story or perspective and integrate their voice, either textually or thematically, into the finished piece.

- Ensuring fair compensation and ongoing consent: This goes beyond a one-time payment. It involves a continuous process of checking in, respecting boundaries, and giving the model agency over how their image is used and displayed.

- Challenging traditional power dynamics: In some cases, artists allow models to direct their own poses or even co-direct the entire creative process, fundamentally subverting the historical gaze.

By adopting these practices, contemporary artists can honor the long tradition of the nude while rectifying its historical imbalances. The body is once again a vessel, but this time, it is a vessel for the subject’s own identity and voice, not just the artist’s vision.

How Does Lime Plaster Lock Pigment Into the Wall Crystal Structure?

The enduring brilliance of Renaissance frescoes is not just a testament to artistic skill but to a remarkable chemical process. The technique, known as buon fresco (“true fresh”), involves painting on a layer of wet lime plaster. The magic lies in the chemistry of carbonation: as the plaster dries, it doesn’t just trap the pigment; it chemically locks it into a newly formed crystal structure, making the painting an integral part of the wall itself.

The process begins with calcium carbonate (limestone or marble), which is heated to produce calcium oxide (quicklime). This is then mixed with water in a process called slaking, creating calcium hydroxide, or lime putty. This putty is mixed with sand to create the final layer of plaster, the intonaco, which is applied to the wall. The artist must work on this wet surface. When the water-based pigments are applied, the calcium hydroxide in the plaster begins to react with carbon dioxide in the air. As the water evaporates, the calcium hydroxide reverts to calcium carbonate, forming transparent calcite crystals that encase the pigment particles. The color is now, quite literally, stone.

This chemical reaction imposes a severe constraint: the artist must finish a section before the plaster dries, a process that can take as little as a few hours. This is why frescoes were painted in sections called giornate (“day’s work”). As one source on the technique notes, artists had only 6-8 hours maximum working time per section. This time pressure is what forced the broad, confident style characteristic of fresco and made meticulous, oil-like detail impossible. The chemistry of the wall dictated the aesthetics of the art.

Case Study: Leonardo’s Disastrous Fresco Experiment

Leonardo da Vinci’s insatiable curiosity and frustration with fresco’s limitations led to one of art history’s most famous technical failures. For The Last Supper (1495-1498), he rejected the fast-paced buon fresco technique. Wanting the slow-drying time and blending capabilities of oil paint, he experimented by applying tempera and oil to a dry wall sealed with a ground of pitch and mastic. While this allowed him to work meticulously for years, his experiment defied the fundamental chemistry of wall painting. Because the paint was merely sitting on the surface instead of being locked within it, it began to flake and deteriorate within his own lifetime, a tragic testament to the unyielding laws of the fresco process.

Understanding fresco is to understand a marriage of art and science. The technique’s permanence is achieved through a chemical transformation that turns pigment and plaster into a single, crystalline entity, forever capturing the artist’s work within the architecture.

Key Takeaways

- Humanism was a philosophical shift that placed human dignity and potential at the center, tasking artists with making this idea visible.

- The body became the primary vehicle for this expression, transforming from a symbol of medieval sin to a “vessel of virtue.”

- Techniques like linear perspective were not just for realism; they were tools to assert the rational human mind as the organizing principle of the world.

Why Did Western Art Focus on Mimesis While Others Chose Abstraction?

The Renaissance cemented a trajectory for Western art that would dominate for the next 500 years: the pursuit of mimesis, the faithful imitation of the observable world. The depiction of the body was central to this project. But why did this path become the primary route for Western art, while other great artistic traditions, such as in the Islamic world, pursued complex abstraction and geometric pattern? The answer lies in the core philosophical premise of humanism itself.

The foundational tenet, inherited from the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras and revitalized by Renaissance thinkers, was that “man is the measure of all things.” This is not an arrogant statement, but an epistemological one. It proposes that human reason and perception are the primary tools for understanding the universe. If the rational, observing human is the central reference point, then the logical function of art becomes the measurement, analysis, and faithful recreation of the world as perceived by that human. Mimesis is the natural artistic consequence of a human-centered worldview.

Man is the measure of all things – this core tenet logically leads to mimesis. If the rational, observing human is central, then art’s primary function becomes the measurement and faithful recreation of the world as perceived by that human.

– Renaissance Philosophy Studies, Humanism and Artistic Representation

In contrast, artistic traditions rooted in aniconic theology took a different path. In many Islamic traditions, for example, the belief in the absolute transcendence and indivisibility of God makes any attempt to depict a divine or human form a potential act of idolatry. Art’s function is not to imitate the fleeting, created world, but to hint at the eternal, underlying order of the universe. This leads to an art of intricate geometry, calligraphy, and arabesque—a visual language that expresses infinity, rhythm, and unity through abstract principles, not through the depiction of a body.

Therefore, the focus on the realistic body in the West was not an inevitable or superior path; it was a choice rooted in a specific philosophical bet on the centrality of the human experience. The Renaissance artist’s obsession with anatomy, perspective, and lifelike portraiture was the direct result of a culture that had decided the most profound truths could be found by looking closely at the human and the world they inhabit.

By understanding this core philosophical choice, we see that the realist bodies of the Renaissance are not just beautiful images, but the conclusion of a powerful cultural argument. To take the next step in your understanding of art history is to continue questioning these foundational principles and exploring the diverse ways humanity has sought to represent its world.